Difference between revisions of "Sandbox"

(version by ChatGPT) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{top}} |

{{top}} |

||

| − | |||

| − | <div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0 0 8px 8px"> |

||

| − | {{pic|Tetreal10bx10d.png|300px}} |

||

| − | <small><center>Real tetration to base \(b=\mathrm e\).<br> |

||

| − | From: Fig.17.2, p.239 in ''Superfunctions''.</center></small> |

||

| − | </div> |

||

'''Tetration''' is the superfunction of the [[exponential]] map. |

'''Tetration''' is the superfunction of the [[exponential]] map. |

||

| − | For a given base \(b\), |

+ | For a given base \(b\), the tetration \(\operatorname{tet}_b\) is defined as the function satisfying the transfer equation |

\[ |

\[ |

||

| − | \operatorname{tet}_b(z+1)=b^{\operatorname{tet}_b(z)} |

+ | \operatorname{tet}_b(z+1) = b^{\operatorname{tet}_b(z)} |

\] |

\] |

||

| − | together with additional normalization conditions that |

+ | together with additional normalization and regularity conditions that select a unique solution among infinitely many possible superfunctions. |

| + | |||

| − | The name “tetration’’ reflects its position as the next operation after exponentiation in the [[hyperoperation]] hierarchy. |

||

| + | The name “tetration’’ reflects its role as the next operation after exponentiation within the [[hyperoperation]] hierarchy. |

||

| − | The most |

+ | The most studied case is the real holomorphic tetration to base \(b=\mathrm e\), written simply as |

\[ |

\[ |

||

\operatorname{tet}(z)=\operatorname{tet}_{\mathrm e}(z). |

\operatorname{tet}(z)=\operatorname{tet}_{\mathrm e}(z). |

||

\] |

\] |

||

| + | |||

| + | <div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:-7px 0px 8px -8px"> |

||

| + | {{pic|Tetreal10bx10d.png|300px}} |

||

| + | <small><center>Real tetration to base \(b=\mathrm e\).<br> |

||

| + | From: Fig.17.2, p.239 in ''Superfunctions''.</center></small> |

||

| + | </div> |

||

==Definition== |

==Definition== |

||

Let \(T_b(z)=b^z\). |

Let \(T_b(z)=b^z\). |

||

| − | A function \(F\) is |

+ | A function \(F\) is a ''superexponential'' (a superfunction of \(T_b\)) if |

| − | \[ |

||

| − | F(z+1)=T_b(F(z)). |

||

| − | \] |

||

| − | A '''tetration''' to base \(b\) is the unique real holomorphic superexponential satisfying the regularity condition |

||

| − | \[ |

||

| − | \lim_{y\to\pm\infty} F(x+\mathrm i y) = \text{finite} |

||

| − | \] |

||

| − | and the normalization |

||

\[ |

\[ |

||

| − | F( |

+ | F(z+1) = T_b(F(z)). |

\] |

\] |

||

| + | A '''tetration''' to base \(b\) is the unique real-holomorphic superexponential for which: |

||

| − | These conditions distinguish tetration from the infinitely many other superfunctions of the same transfer equation. |

||

| + | |||

| + | # the limits |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| + | \lim_{y\to\pm\infty} F(x+\mathrm i y) |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | remain finite (regularity at the imaginary infinities), |

||

| + | # the normalization |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| + | F(0)=1 |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | holds. |

||

| + | |||

| + | These conditions remove the otherwise infinite freedom in solutions to the transfer equation. |

||

==Properties== |

==Properties== |

||

| − | For the principal tetration \(\operatorname{tet}_b\) |

+ | For the principal tetration \(\operatorname{tet}_b\): |

| − | * ** |

+ | * **Transfer equation** |

\[ |

\[ |

||

\operatorname{tet}_b(z+1)=b^{\operatorname{tet}_b(z)}. |

\operatorname{tet}_b(z+1)=b^{\operatorname{tet}_b(z)}. |

||

| Line 46: | Line 52: | ||

* **Derivative at the fixed point** |

* **Derivative at the fixed point** |

||

| − | + | Let \(L\) satisfy \(L = b^L\). Then |

|

\[ |

\[ |

||

| − | \operatorname{tet} |

+ | \operatorname{tet}_b'(0)=L. |

\] |

\] |

||

* **Analyticity** |

* **Analyticity** |

||

| − | For \(1< b < \mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), the tetration to base \(b\) extends to an entire function. |

+ | For \(1 < b < \mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), the tetration to base \(b\) extends to an entire function. |

| − | For |

+ | For \(b > \mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), branch singularities appear, and a global entire tetration is impossible. |

| + | |||

| + | ==Regularity in the base== |

||

| + | The tetration depends smoothly on the base \(b\) for |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| + | 1 < b < \mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}. |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | Within this range, the exponential map \(z\mapsto b^z\) has two attracting fixed points, allowing construction of an entire Abel function and an entire tetration. |

||

| + | |||

| + | At the critical base, the two fixed points merge, and the dynamical structure changes. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Singularity at the critical base \(b = 1/\mathrm e\)== |

||

| + | The point |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| + | b = \frac{1}{\mathrm e} |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | is a branch point of the exponential map in the parameter \(b\). |

||

| + | Although tetration is smooth for \(b>1/\mathrm e\), this regularity does *not* guarantee holomorphic extendability across the branch point. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Important observations: |

||

| + | |||

| + | * When the base parameter \(b\) is continued into the complex plane, the behavior around \(b=1/\mathrm e\) becomes path-dependent. |

||

| + | * Continuation of tetration above and below the branch point generally does not give the same result — the continuation is multivalued. |

||

| + | * The situation is analogous to the relation between the [[Exponential integral]] \(\operatorname{Ei}\) and \(E_1\): one can smoothly approach the singularity from either side, but no single global holomorphic branch exists. |

||

| + | * For tetration, the complication is deeper because the function depends on two variables \((b,z)\); nonetheless, \(b=1/\mathrm e\) remains a limiting point for the tetrations defined on both sides. |

||

| + | |||

| + | This is one of the important unresolved structural problems of tetration theory. |

||

==Complex structure== |

==Complex structure== |

||

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0 0 8px 8px"> |

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0 0 8px 8px"> |

||

{{pic|Ackerplot.jpg|300px}} |

{{pic|Ackerplot.jpg|300px}} |

||

| − | <small><center> |

+ | <small><center>Ackermann-family functions. |

| + | Natural tetration (dashed) and other Ackermann-like functions.<br> |

||

From: Fig.19.7, p.266 in ''Superfunctions''.</center></small> |

From: Fig.19.7, p.266 in ''Superfunctions''.</center></small> |

||

</div> |

</div> |

||

| − | The complex dynamics of \(z\mapsto b^z\) |

+ | The complex analytic structure of tetration is governed by the dynamics of \(z\mapsto b^z\). |

| − | For \(1<b<\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), the |

+ | For \(1<b<\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), the map has two attracting fixed points. |

| − | This allows |

+ | This allows one to construct an Abel function that is analytic on the entire plane and thus an entire tetration. |

| + | |||

| − | At the critical base \(b=\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), these fixed points collide (bifurcation), and above this threshold, the dynamics become repelling, producing complex branches. |

||

| + | At the critical base \(b=\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), the two fixed points collide (parabolic bifurcation). |

||

| + | For \(b>\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), both fixed points become repelling, and the Abel function — hence tetration — develops branch points and cannot be entire. |

||

==Relation to superfunctions== |

==Relation to superfunctions== |

||

| + | A superfunction \(F\) of \(T_b\) satisfies |

||

| − | Tetration is the ''canonical'' superfunction of the exponential. |

||

| − | Any superfunction \(F\) of \(T_b(z)=b^z\) satisfies the transfer equation |

||

\[ |

\[ |

||

F(z+1)=b^{F(z)}. |

F(z+1)=b^{F(z)}. |

||

\] |

\] |

||

| − | Among these, the tetration is the uniquely normalized superfunction that is: |

||

| − | * real on the real axis, |

||

| − | * holomorphic in a vertical strip, |

||

| − | * smooth at \(\pm\mathrm i\infty\), |

||

| − | * normalized by \(F(0)=1\). |

||

| + | Among the infinitely many such functions, the tetration is selected by: |

||

| − | Other superexponentials differ by periodic or quasiperiodic distortions. |

||

| + | |||

| + | * realness on the real axis, |

||

| + | * holomorphy in a vertical strip, |

||

| + | * regularity at \(+\mathrm i\infty\) and \(-\mathrm i\infty\), |

||

| + | * normalization at \(z=0\). |

||

| + | |||

| + | All other superexponentials differ by periodic or quasiperiodic distortions. |

||

==Inverse: Abel function== |

==Inverse: Abel function== |

||

| − | The inverse of tetration is the [[Abel function]] (ArcTetration), denoted |

+ | The inverse of tetration is the [[Abel function]] (ArcTetration), denoted \(\operatorname{ate}_b\). |

| − | It satisfies |

+ | It satisfies |

\[ |

\[ |

||

| − | \operatorname{ate}_b(b^z)=\operatorname{ate}_b(z)+1, |

+ | \operatorname{ate}_b(b^z) = \operatorname{ate}_b(z) + 1, |

\] |

\] |

||

| + | with |

||

| − | with normalization \(\operatorname{ate}_b(1)=0\). |

||

| + | \[ |

||

| − | For the natural exponential, this becomes |

||

| + | \operatorname{ate}_b(1)=0. |

||

| + | \] |

||

| + | |||

| + | For the natural exponential: |

||

\[ |

\[ |

||

| − | \operatorname{ate}(\exp(z))=\operatorname{ate}(z)+1. |

+ | \operatorname{ate}(\exp(z)) = \operatorname{ate}(z) + 1. |

\] |

\] |

||

==Iterates== |

==Iterates== |

||

| − | + | Tetration and ArcTetration provide analytic extensions of integer iteration. |

|

| − | For the \(n\)-th iterate of the exponential |

+ | For the \(n\)-th iterate of the exponential: |

\[ |

\[ |

||

| − | \exp_b^n(z)=\operatorname{tet}_b\!\ |

+ | \exp_b^n(z) = \operatorname{tet}_b\!\big(n + \operatorname{ate}_b(z)\big), |

\] |

\] |

||

| − | + | valid for real or complex \(n\). |

|

| − | |||

| − | This gives a smooth functional continuation of exponentiation to non-integer “heights’’. |

||

==Special cases== |

==Special cases== |

||

| − | <div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin: |

+ | <div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:-30px 0 8px 8px"> |

| − | {{pic|E1efig09abc1a150.png| |

+ | {{pic|E1efig09abc1a150.png|480px}} |

<small><center>Tetration near the critical base \(b=\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\).<br> |

<small><center>Tetration near the critical base \(b=\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\).<br> |

||

From: Fig.17.4, p.245 in ''Superfunctions''.</center></small> |

From: Fig.17.4, p.245 in ''Superfunctions''.</center></small> |

||

</div> |

</div> |

||

| − | ===Base \( |

+ | ===Base \(\sqrt{2}\)=== |

| + | A classical example of an entire tetration, used extensively in early numerical work. |

||

| − | This base is the threshold at which the exponential map changes from having two attracting fixed points to having none. |

||

| − | The tetration at this base has unusual properties, such as: |

||

| − | * extremely slow growth near its fixed point, |

||

| − | * increased sensitivity to initial conditions, |

||

| − | * non-entire analytic structure. |

||

| − | ===Base \(b=\mathrm e\)=== |

+ | ===Base \(b= \mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\)=== |

| + | This “critical base’’ marks the transition where the fixed points of \(z\mapsto b^z\) merge. |

||

| − | The standard tetration \(\operatorname{tet}(z)\) is real and smooth on the entire real line. |

||

| + | Properties include: |

||

| − | Its values decrease towards the lower fixed point of the exponential as \(z\to-\infty\), and blow up super-exponentially as \(z\to+\infty\). |

||

| + | * extremely slow growth near the fixed point, |

||

| − | ==Historical remarks== |

||

| + | * non-entire analytic continuation, |

||

| − | The modern construction of real analytic tetration was developed by: |

||

| + | * delicate dependence on initial conditions. |

||

| − | * E. Schröder and G. Koenigs (19th century) — regular iteration theory |

||

| − | * J. Kneser (1949) — analytic solution for base \(b=\mathrm e\) |

||

| − | * D. Kouznetsov and H. Trappmann (2009–2024) — complex extension, superfunctions, explicit computation methods |

||

| + | ===Base 2=== |

||

| − | A unified presentation is given in the monograph ''[[Superfunctions]]''. |

||

| + | An important superexponential used in comparisons with hyperoperators. |

||

| − | == |

+ | ===Natural tetration=== |

| + | The principal tetration \(\operatorname{tet}(z)\) is real-analytic on the real axis. |

||

| + | As \(z\to -\infty\), it approaches the lower fixed point of \(\exp(z)\). |

||

| + | As \(z\to +\infty\), it grows faster than any finite exponential tower. |

||

| + | |||

| + | ==Figures== |

||

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0 0 8px 8px"> |

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0 0 8px 8px"> |

||

{{pic|B271t.png|300px}} |

{{pic|B271t.png|300px}} |

||

| − | <small><center> |

+ | <small><center>Tetration and its inverse (ArcTetration).<br> |

From: Fig.14.4, p.203 in ''Superfunctions''.</center></small> |

From: Fig.14.4, p.203 in ''Superfunctions''.</center></small> |

||

</div> |

</div> |

||

| − | |||

| − | Some characteristic graphs: |

||

| − | |||

| − | * Real tetration \(\operatorname{tet}(x)\) |

||

| − | * Complex level sets of tetration |

||

| − | * Abel function \(\operatorname{ate}(x)\) |

||

| − | * Iterates \(\exp^n(x)\) for fractional \(n\) |

||

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0 0 8px 8px"> |

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0 0 8px 8px"> |

||

| Line 149: | Line 180: | ||

</div> |

</div> |

||

| + | ==Conceptual illustration== |

||

| − | ==Humor== |

||

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0 0 8px 8px"> |

<div class="thumb tright" style="float:right; margin:0 0 8px 8px"> |

||

| − | {{pic|BlackSheep.png| |

+ | {{pic|BlackSheep.png|280px}} |

| − | <small><center> |

+ | <small><center>Heuristic “half-sheep’’ illustration.<br> |

| + | From: Fig.15.6, p.218 in ''Суперфункции'' (2014).</center></small> |

||

</div> |

</div> |

||

| + | |||

| + | This cartoon illustrates a philosophical point in tetration theory: |

||

| + | heuristic assumptions that appear “obvious’’ (e.g., that the right side of a sheep has the same color as the left) may be false without rigorous proof. |

||

| + | |||

| + | Likewise, assumptions about tetration — such as smoothness in both arguments \((b,z)\), or holomorphic extendability across \(b=1/\mathrm e\) — require careful justification. |

||

| + | The cartoon emphasizes that the behavior of superexponentials around their branch points is subtler than it may first appear. |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

| Line 159: | Line 197: | ||

D. Kouznetsov. ''Superfunctions''. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2020. |

D. Kouznetsov. ''Superfunctions''. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2020. |

||

| + | All cited figures except the last are taken from this monograph. |

||

| − | Includes all figures cited above. |

||

| + | |||

| + | D. Kouznetsov. ''Суперфункции''. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2014. |

||

| + | Figure 15.6 (the “half-sheep’’) is taken from this edition. |

||

{{fer}} |

{{fer}} |

||

==Keywords== |

==Keywords== |

||

| − | «[[Superfunction]]», «[[Exponential]]», «[[Logarithm]]», |

+ | «[[Base e1e]]», «[[Base sqrt2]]», «[[Superfunction]]», «[[Exponential]]», «[[Logarithm]]», |

| − | «[[Tetration]]», «[[ate]]», «[[Abel function]]», |

+ | «[[Tetration]]», «[[ate]]», «[[Abel function]]», «[[Transfer equation]]», «[[Iterates]]». |

| − | «[[Transfer equation]]», «[[Iterates]]». |

||

[[Category:Superfunction]] |

[[Category:Superfunction]] |

||

Revision as of 00:20, 12 December 2025

Tetration is the superfunction of the exponential map. For a given base \(b\), the tetration \(\operatorname{tet}_b\) is defined as the function satisfying the transfer equation \[ \operatorname{tet}_b(z+1) = b^{\operatorname{tet}_b(z)} \] together with additional normalization and regularity conditions that select a unique solution among infinitely many possible superfunctions.

The name “tetration’’ reflects its role as the next operation after exponentiation within the hyperoperation hierarchy.

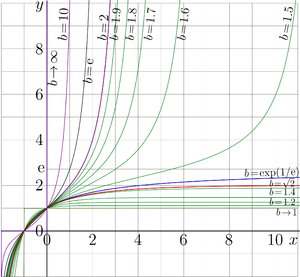

The most studied case is the real holomorphic tetration to base \(b=\mathrm e\), written simply as \[ \operatorname{tet}(z)=\operatorname{tet}_{\mathrm e}(z). \]

Definition

Let \(T_b(z)=b^z\). A function \(F\) is a superexponential (a superfunction of \(T_b\)) if \[ F(z+1) = T_b(F(z)). \]

A tetration to base \(b\) is the unique real-holomorphic superexponential for which:

- the limits

\[

\lim_{y\to\pm\infty} F(x+\mathrm i y)

\]

remain finite (regularity at the imaginary infinities),

- the normalization

\[ F(0)=1 \] holds.

These conditions remove the otherwise infinite freedom in solutions to the transfer equation.

Properties

For the principal tetration \(\operatorname{tet}_b\):

- **Transfer equation**

\[ \operatorname{tet}_b(z+1)=b^{\operatorname{tet}_b(z)}. \]

- **Derivative at the fixed point**

Let \(L\) satisfy \(L = b^L\). Then \[ \operatorname{tet}_b'(0)=L. \]

- **Analyticity**

For \(1 < b < \mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), the tetration to base \(b\) extends to an entire function. For \(b > \mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), branch singularities appear, and a global entire tetration is impossible.

Regularity in the base

The tetration depends smoothly on the base \(b\) for \[ 1 < b < \mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}. \] Within this range, the exponential map \(z\mapsto b^z\) has two attracting fixed points, allowing construction of an entire Abel function and an entire tetration.

At the critical base, the two fixed points merge, and the dynamical structure changes.

Singularity at the critical base \(b = 1/\mathrm e\)

The point \[ b = \frac{1}{\mathrm e} \] is a branch point of the exponential map in the parameter \(b\). Although tetration is smooth for \(b>1/\mathrm e\), this regularity does *not* guarantee holomorphic extendability across the branch point.

Important observations:

- When the base parameter \(b\) is continued into the complex plane, the behavior around \(b=1/\mathrm e\) becomes path-dependent.

- Continuation of tetration above and below the branch point generally does not give the same result — the continuation is multivalued.

- The situation is analogous to the relation between the Exponential integral \(\operatorname{Ei}\) and \(E_1\): one can smoothly approach the singularity from either side, but no single global holomorphic branch exists.

- For tetration, the complication is deeper because the function depends on two variables \((b,z)\); nonetheless, \(b=1/\mathrm e\) remains a limiting point for the tetrations defined on both sides.

This is one of the important unresolved structural problems of tetration theory.

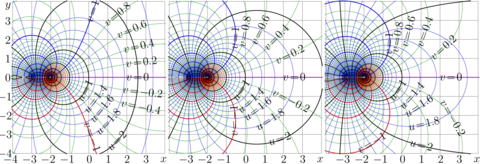

Complex structure

Natural tetration (dashed) and other Ackermann-like functions.

The complex analytic structure of tetration is governed by the dynamics of \(z\mapsto b^z\). For \(1<b<\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), the map has two attracting fixed points. This allows one to construct an Abel function that is analytic on the entire plane and thus an entire tetration.

At the critical base \(b=\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), the two fixed points collide (parabolic bifurcation). For \(b>\mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\), both fixed points become repelling, and the Abel function — hence tetration — develops branch points and cannot be entire.

Relation to superfunctions

A superfunction \(F\) of \(T_b\) satisfies \[ F(z+1)=b^{F(z)}. \]

Among the infinitely many such functions, the tetration is selected by:

- realness on the real axis,

- holomorphy in a vertical strip,

- regularity at \(+\mathrm i\infty\) and \(-\mathrm i\infty\),

- normalization at \(z=0\).

All other superexponentials differ by periodic or quasiperiodic distortions.

Inverse: Abel function

The inverse of tetration is the Abel function (ArcTetration), denoted \(\operatorname{ate}_b\). It satisfies \[ \operatorname{ate}_b(b^z) = \operatorname{ate}_b(z) + 1, \] with \[ \operatorname{ate}_b(1)=0. \]

For the natural exponential: \[ \operatorname{ate}(\exp(z)) = \operatorname{ate}(z) + 1. \]

Iterates

Tetration and ArcTetration provide analytic extensions of integer iteration. For the \(n\)-th iterate of the exponential: \[ \exp_b^n(z) = \operatorname{tet}_b\!\big(n + \operatorname{ate}_b(z)\big), \] valid for real or complex \(n\).

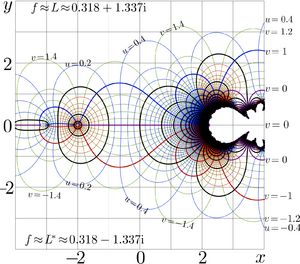

Special cases

From: Fig.17.4, p.245 in Superfunctions.

Base \(\sqrt{2}\)

A classical example of an entire tetration, used extensively in early numerical work.

Base \(b= \mathrm e^{1/\mathrm e}\)

This “critical base’’ marks the transition where the fixed points of \(z\mapsto b^z\) merge. Properties include:

- extremely slow growth near the fixed point,

- non-entire analytic continuation,

- delicate dependence on initial conditions.

Base 2

An important superexponential used in comparisons with hyperoperators.

Natural tetration

The principal tetration \(\operatorname{tet}(z)\) is real-analytic on the real axis. As \(z\to -\infty\), it approaches the lower fixed point of \(\exp(z)\). As \(z\to +\infty\), it grows faster than any finite exponential tower.

Figures

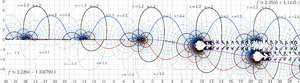

Conceptual illustration

This cartoon illustrates a philosophical point in tetration theory: heuristic assumptions that appear “obvious’’ (e.g., that the right side of a sheep has the same color as the left) may be false without rigorous proof.

Likewise, assumptions about tetration — such as smoothness in both arguments \((b,z)\), or holomorphic extendability across \(b=1/\mathrm e\) — require careful justification. The cartoon emphasizes that the behavior of superexponentials around their branch points is subtler than it may first appear.

References

D. Kouznetsov. Superfunctions. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2020. All cited figures except the last are taken from this monograph.

D. Kouznetsov. Суперфункции. Lambert Academic Publishing, 2014. Figure 15.6 (the “half-sheep’’) is taken from this edition.

Keywords

«Base e1e», «Base sqrt2», «Superfunction», «Exponential», «Logarithm», «Tetration», «ate», «Abel function», «Transfer equation», «Iterates».